The Lead

In the last two months, I’ve tried to write this blog post a few times. I’ve started, stopped, revised, and ultimately deleted. As the weeks piled on, I’ve scribbled down ideas just to have a conversation with someone that made them moot. I’ve struggled to pull out the common thread, a clear theme, a working framework to understand my experience in Latvia thus far.

I haven’t come to any conclusion except that Latvia, and especially the specific area of Latvia in which I’m living, are much more complex than I initially expected. Perhaps the arrogance of comparison — that of the obviously foreign Kazakhstan, where I used to live, and the seemingly European Latvia — got the best of me. In this blog post, I hope to explain why my thinking has changed.

My grandfather worked with maps. I think it’s from him that I find it helpful to use geography as a basis for understanding places. I start from afar and zoom in.

First, we have “Eastern Europe,” which is an amorphous label that encapsulates a set of countries west of Russia, south of Scandinavia, north of the Mediterranean, and east of, well, that gets complicated but basically Germany. We all have an idea of “eastern Europe,” but, we can be honest, it’s usually just a way to differentiate between the countries that American college juniors study abroad in and the less developed rest to which those same students sometimes travel for cheap vacations during their abroad year. Indeed, in a recent interview with Deep Baltic, Jacob Mikanowski, a historian and author of Goodbye Eastern Europe, discussed how the label “Eastern Europe” is used by outsiders to group together countries that see themselves as distinctly different from each other.

Zoom in — we see the Baltics: Estonia at the top, Latvia in the middle, Lithuania on the bottom bordering Poland, Belarus, and Kaliningrad in the south. Even though these three countries are often grouped together, they’re pretty different.

Estonia has made a hard pivot from the Soviet to the Scandinavian. Its people are much more Nordic-looking. They speak Estonian, which is on a completely different language tree than the rest of Eastern Europe and is most closely related to Finnish. Tallinn, Estonia’s capital, apparently is flush with tech start-ups. Famously, Skype is headquartered there.

Lithuania, on the other hand, is closer to what Americans traditionally think of when they think of “Eastern Europe.” Still, there are some distinct factors worth noting. Lithuania is predominantly Catholic and has historically been more closely linked to Poland. Lithuania is also more ethnically unified than Latvia, with 85 percent of the population identifying as ethnically Lithuanian.

Finally, we have Latvia. As one of my students complained to me recently, Latvia often ranks last of the three Baltics. It’s poorer, more violent, more dangerous to drive in, more obese, and less unified ethnically than either of its neighbors. While there are majority-Russian speaking areas in all three countries, Latvia has by far the most native-Russian speakers (around 40%).

Zoom in — in eastern Latvia right along the Russian border, you’ll find the region of Latgale. Latgale is culturally, linguistically, ethnically, and historically distinct from the rest of Latvia. Its history reflects the rise and fall of nearby empires. In the second half of the 16th century, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, also known as the First Polish Republic, annexed Latgale. Two hundred years of Polish rule and influence commenced. Then Poland was partitioned for the first of many times, and the Russian Empire took over Latgale in 1772. It would remain under Russian rule until the October Revolution in 1917 provided an opening for Latvian nationalists.

In her book Among the Living and the Dead, Inara Verzemnieks sums up the opportunity and jubilation in Latvia after World War I, during which Latvia was not ruled by a foreign empire for the first time in centuries. She writes, “One by one, the distractions mount, until suddenly there’s a pause long enough for a man to take the stage of the national theater in Riga to announce, ‘This place is real, this country is real. It exists.’”

After beating back the Red Army, the first newly independent Latvian state was established, and Latgale has been grouped in with the other ethnic Latvians, not Russians, not Poles. But that history, of course, could never be erased. And though Latgale experienced the same fate as the rest of Latvia — invasion by the Soviets during World War II, then Nazi invasion and rule, followed by a second invasion by the Red Army that would last until the end of the Soviet Union — it has remained distinct from the rest of the country.

Unlike the rest of Latvia, which is mostly Lutheran due to historic German influence, Latgale is predominantly Catholic; however, it also includes large Russian Orthodox and Old Believer minorities. Because it was once a part of Poland, there is a considerable Polish population, and many people, especially older people, can still speak Polish. But perhaps most relevant to today’s world, because Latgale is closest to Russia and was part of the Russian Empire for longer, it has the highest percentage of Russian speakers of any region in Latvia. To make matters even more complicated, Latgale also has its own distinct language, Latgalian, which is still spoken by about 100,000 people, including many of my students and their parents. (Latgalian is related to Latvian but has some pretty considerable differences: whether it’s a language or dialect is an ongoing debate.) Around town, store owners put up stickers on the doors of their businesses to indicate that they speak Latgalian.

Zoom in — we’re in Rēzekne now. Looking down from the viewpoint of satellites orbiting about 400 miles above earth, the city may seem large for a population of under 30,000. On the ground, it feels like more people should live here given the infrastructure. And that’s because it once had more people, not too long ago. Built on seven hills, one of which was the site of a great castle that now lies in ruins, Rēzekne bloomed during the Russian Empire since both the Moscow-Ventspils and Saint Petersburg-Warsaw railroads intersected here.

Known as “the heart of Latgale,” Rēzekne — like much of the region and the country — was largely destroyed during World War II, both in terms of population and people. Rēzekne’s Jewish population, which had made up to 60 percent of the city in the 1800s, was almost completely wiped out by Nazis and Latvian collaborators. Walking around town, there are a few memorials at the sites of massacres, and on a hill at the edge of the city, there is a Jewish cemetery filled with generations of families.

Though two thirds of the buildings in Rēzekne were destroyed during the war, Rēzekne was rebuilt and industrialized during the fifty years of Soviet rule. Rēzekne grew from a post-war population of just 5,000 to, by some estimates, over 40,000 buoyed by a canned milk factory, a milking equipment factory, and a building equipment factory.

Today, I can see the smokestack of one of Rēzekne’s formerly bustling manufacturing plants from my window. After the fall of the Soviet Union, most of Rēzekne’s prized factories were privatized, sold, and then closed. During the Great Recession, the unemployment rate rose above 20 percent and stayed above 10 percent for most of the next decade. According to the Latvian government data, Rēzekne’s unemployment rate was 11.3 percent in 2023, down from 12.6 percent in 2022.

In the darkness of the early morning, parents drop their kids off at school, former factory workers clock in at the grocery stores, and a few people may be stumbling around, either still blitzed from the night before or already started with the day’s binge. Rēzekne is one of many places that got the raw side of the deal when the Soviet Union fell, Latvia joined the EU, and the economy globalized. Hemorrhaging people and money from its tax base, it’s not clear whether the city can rebound or will regress back into a small town — perhaps it’s natural state but for the Soviet planned economy and crisscrossing train tracks to destinations in Russia people used to be able to visit freely.

After a business deal with a Russian hockey team that involved the construction of a state-of-the-art sauna and hotel went belly up because Russia invaded Ukraine, the Rēzekne municipal government has been left with an empty bathhouse and crippling debt. The former mayor and architect of the deal apparently mismanaged four million euros of city funds and was removed by officials in Riga. Despite also being investigated for corruption (his family owns the construction company that gets most of the building deals in town), he is running for mayor again. According to vibes around town and some online poll that my Russian tutor told me about, he’s expected to win. (More on him to come in future posts.)

Earlier this fall, the Baltic News Network reported that city administrators feared they would not have the budget to pay for basic services, like clearing the streets, especially if it will be a winter of heavy snows.

Zoom in — in the center of Rēzekne, you can see a physical manifestation of Latvian culture and, down the street, an indentation in the ground. This is the tale of two statues.

The first, Latgales Māra — also known as “Latgale’s Mother” or United for Latvia — features a woman holding up a large cross to the sun. At her feet, two children hold her up. One gives her a crown of oak leaves. First erected during the interwar independent Latvian republic, Latgales Māra represents the victory of Latvians over foreign powers. One year later, the Soviets brought down the monument. It briefly was reconstructed in 1943 before the Soviets once again took it down in 1950. But the people of Rēzekne never forgot the statue. For 42 years, they waited. Then the Soviet Union fell, and residents scraped together the funds to put up Latgale’s Mother once again.

Just down the street, there is an empty plot next to the bus station. This used to be the site of the Soviet War monument known locally as алёша (alyosha). A towering soldier with a square build, алёша was one of many Soviet monuments that came under new scrutiny after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The mayor (yes, the same one as previously mentioned) called the destruction of the statue “barbarism.” He petitioned the government in Riga to allow the city to simply move алёша to the local cemetery, which his proposal was rejected. Алёша now sits in storage at the Occupation Museum of Jelgava.

Zoom in — in one of the many block-like five-story apartment buildings in the city, down the street from the Finnish McDonald’s knockoff chain called Hesburger, you’ll find me, where I’m trying to make sense of all of this.

It’s been tricky. Certainly trickier than I thought. I’ve never been in a place where language is as much of a lightning rod. I’m here, in part, because I wanted to improve my Russian. But I also want to respect the Latvian population by showing that I’m trying to learn some of their language, which they hold in extremely high regard.

The result has been frequent language paralysis in everyday situations.

An example from a recent trip to the hunting outfitter store to buy gloves:

I’m staring at two pairs of gloves for what feels like 20 minutes, paralyzed by indecision. I decide to go up to the guy working who has been watching me this whole time (I’m the only person in the store).

I walk up to him, thinking about what language to even begin this interaction in, then…

Him: “Ludzu” (Language: Latvian; translation in this case, “yes,” or “please” - as in, “please what can I help you with?”)

Me, confused, stuck. This is not how things usually start, panic…

Me: “Ludzu” (Language: Latvian; translation, “please?”)

He stares at me, confused. He basically just said, “please,” and then I said, “please” back. Switch to Russian.

Me: “Вы говорите по-английски?” (Language: Russian; translation, “Do you speak English?”)

Him: “Uh little uh bit”

Me: “Что лучше?” (Language: Russian; translation: “Which is better?”)

I hold up both gloves. He points to a pair on the left.

Me: “Paldies” (Language: Latvian; translation: “Thank you”)

Walking out of the store with my new gloves (13 euro), I shook my head and laughed. Why did I respond with “please” when he said “please”? Why did I ask if he spoke English in Russian? Why didn’t I just speak English once he said he knew some English?

Of course, none of this really matters, but imagine this happening all the time, every day, in every interaction you have all day. Checking out at the grocery store. Buying bus tickets. Greeting colleagues. Ordering a beer. At the local coffee shop, I speak English with one barista and with the other I greet in Latvian and order in Russian. Sometimes, nothing comes out. Air just slowly is released through my mouth as I try to figure out what I’m trying to say and in which language to speak.

The locals, however, seem to have adapted to this linguistic minefield with deft and ease. A few Latvians have told me that even if they’re in a group of five Latvians and one Russian, the group will speak Russian. On the other hand, many of my students refuse to speak Russian anymore. In some of my classes, the students group themselves not by gender or popularity or any other familiar sorting factor. Instead, they sit with the other students who speak their preferred language. During group work, I hear Russian on the right and Latvian on the left (even though, of course, everyone should be speaking English in English class). Even more mind boggling, many conversations flip between the two languages freely. Sometimes, one speaker will speak Russian, the other will reply in Latvian, and neither will change. They’ll just go on: speaking, translating the response in their head, switching languages, speaking again. Other times, conversations will flip between Russian and Latvian for seemingly no discernible reason. As someone trying to learn Russian, there’s nothing more disorienting than starting to eavesdrop on a conversation, not picking up on anything, and then realizing that the speakers have switched to Latvian.

There are, however, some instances of language universality. Everyone says “sorry” in English. Everyone swears in Russian.

The News

Evan Gershkovich’s first piece published in the WSJ after he was released from detention in Russia. It’s an interesting look at the elite unit within the Russian FSB called the Department for Counterintelligence Operations, which carries out much of the harassment and detention of foreigners and dissenters. Among many of the interesting details: two of Gershkovich’s colleagues were openly followed in Vienna and Washington while reporting this story. In Latvia, it’s not a question that there are spies among the civilian population, though I have doubts about whether any are placed in Rēzekne.

A really good long read from James Pogue that goes into the U.S. dollar system, NATO, Steve Bannon’s scary plans for the future, and the emerging global order that will no longer be monopolar. It’s a great snapshot of how people on both sides of the Atlantic and both sides of the political system are thinking about our geopolitical moment. It came out before Trump was elected again but seems even more relevant now.

An interesting article from The Guardian about how even progressive Russians, many of whom have left Russia in recent years, continue to propagate Russian supremacy inadvertently through culture. This is something that’s not talked about a lot. The whole world knows about Russian military power, but Russian culture has also been used as a weapon to flatten out minority cultures during Soviet times and today. The Russian Federation has great ethnic diversity — from Tartars to Yakuts to Ingrian Finns — but in the West, it seems like a safe bet that we don’t even know these people exist. Even continuing to group all countries that used to be part of the Soviet Union as commonly “post-Soviet,” which is something I’m guilty of doing, gives Russia undue power.

Personals

Though this blog is super overdue, I swear I haven’t just been sitting at home doing nothing. I’ve been writing for a few other places:

Sometime in October, I was in a bookstore in Riga and picked up a paper zine called Rose-Tinted Glasses. The zine, which publishes all sorts of pieces “questioning the current climate (and hierarchies) of the art world,” had a call for an open submission on the back. I had the time, so I wrote up a short story (very short - 500-600 words), and sent it to the editors. I’m happy to say that it’ll be in the next issue, which will be circulated in Riga, Vilnius, and maybe Tallinn. I’ll link it in my next post.

I’m writing a short piece for the Princeton in Asia (PiA) yearly newsletter celebrating the 30-year anniversary of PiA working with KIMEP University, where I used to work as an English lecturer. The piece is also going to be short (also just about 600 words), but it’s been a great experience to go back and interview so many former PiA fellows who lived in Kazakhstan. I thought Kazakhstan was pretty wild at times when I lived there a couple years ago, but then I heard the stories from fellows who were there in the 1990s.

I wrote a very short and very basic article for the local newspaper, Rēzeknes Novads, which publishes biweekly in both Russian and Latvian. After sending it to the editors and receiving no response for two months, a student came up to me last week and told me that she read my article in the newspaper. I asked her what she thought of it, and she said it sounded a little bit like ChatGPT wrote it (it was likely translated using some sort of AI translation from English to Russian and Latvian, so that tracks). It was paired with another short article explaining who I am and what I’m doing here.

And then finally, I’ve been working on some pitches about life and politics in Latvia. I think I got stymied by the holiday season, but I’ve been to the border with Russia four times, where I’ve been interviewing truck drivers. Hopefully, those interviews will turn into a proper, commissioned story in the spring.

Non-writing stuff:

I’ve played more volleyball in the last three months than I’ve played in my entire life before arriving in Latvia. Every Tuesday and Thursday, I walk the half hour to volleyball practice on the other side of town. I play volleyball for three hours (7-10 p.m.) and then walk home. It’s a funny scene. We play in an elementary school gym. There are students from the local university, some of my students from one of the local high schools, and a group of older guys from Ludza, Latvia’s oldest town, which is about 30 minutes away by car, all playing together. I’m the only English speaker, which has led to some unfortunate situations. I learned the Latvian phrases for “play it” and “me” (as in “I’m hitting this one”) by, of course, doing exactly the opposite of what people were calling for me to do. Walking home, I have to cross the train tracks that bisect the city. There is a bridge, but all the locals prefer to just walk right across the active tracks.

Two parties. The first — parents and teachers party in early December. I brought a fruit salad. No one ate it. I was cajoled into dancing with my students’ moms as they got increasingly drunk. The second — some of my students invited me to the university Christmas party. It was almost identical to the parents’ party. My students gave me some moonshine to drink. Fueled by their home brew, a few boys who are usually quiet in class had long conversations with me. I declined a couple of my female students’ requests to dance and left before 2 a.m.

Other important images from the last few months:

P.S.

Please email/reach out with questions and typos. A goal for the new year: shorter posts, more frequently.

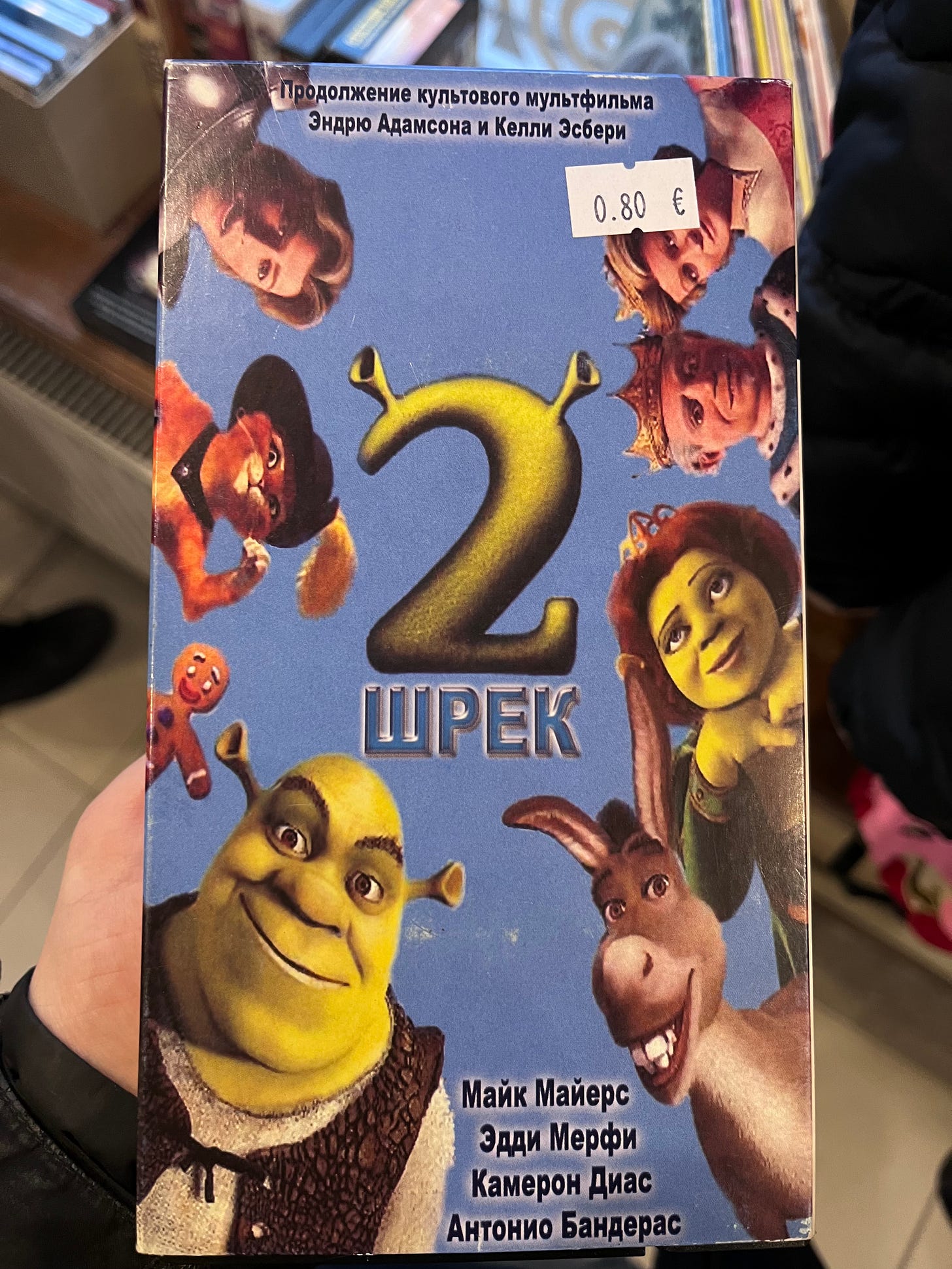

Greatly enjoyed reading this as well as the Russian shrek! Keep it coming man!